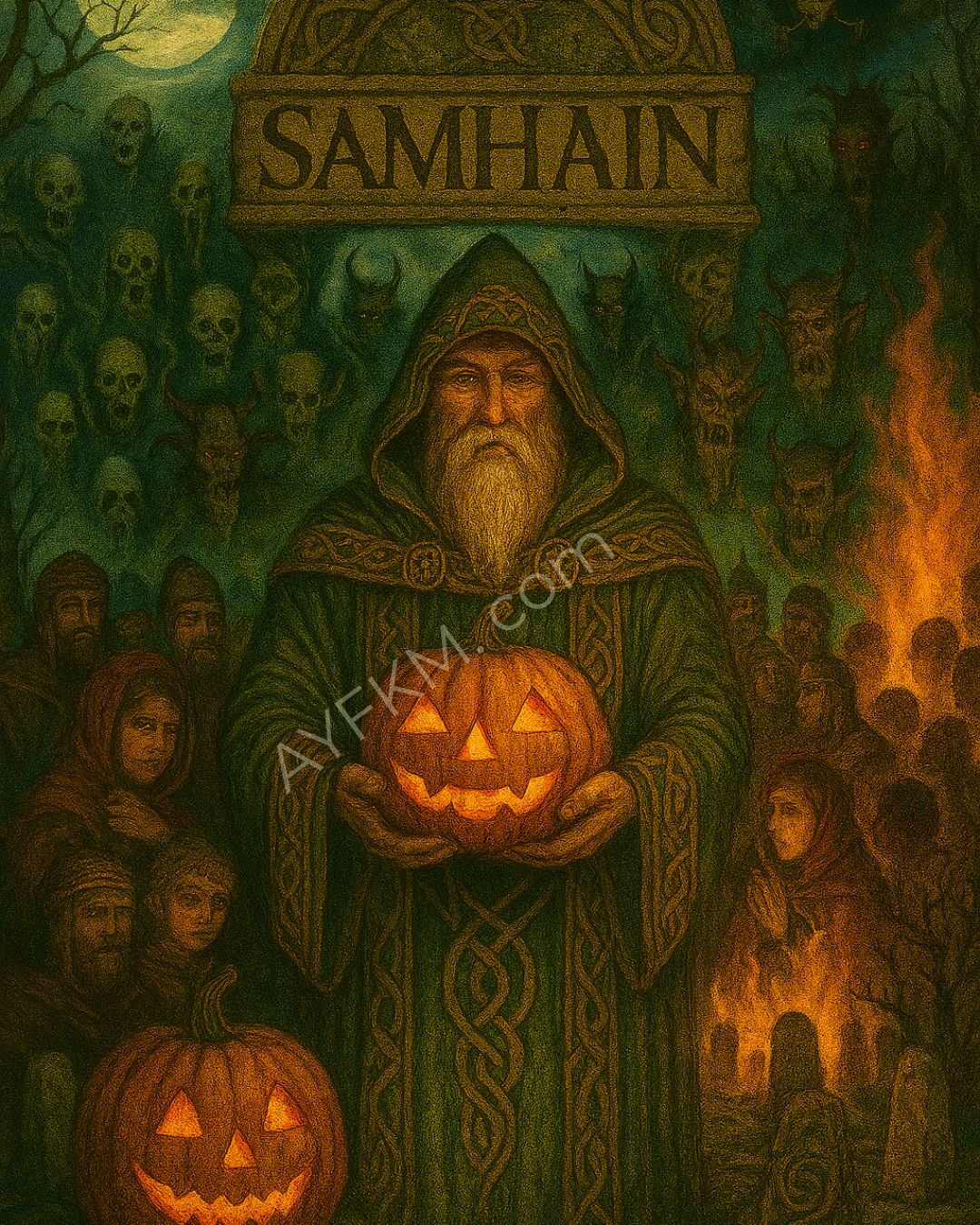

Not Just Another Pagan Party: How Samhain Became the Halloween we Forgot

Long before Halloween became synonymous with plastic skeletons and pumpkin spice, it was Samhain (pronounced SOW-in)—the most spiritually potent festival in the ancient Celtic calendar. Celebrated from sunset on October 31st through November 1st, Samhain marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of the dark half of the year. It wasn’t just seasonal; it was cosmological.

Image Credit: AYFKM.com

The Celts believed that during Samhain, the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead grew thin—so thin that spirits, ancestors, and otherworldly beings could cross over. This wasn’t superstition. It was survival.

Samhain was one of the four major fire festivals in the Celtic Wheel of the Year, alongside Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh. It marked the death of the sun god and the descent into winter—a time when crops had been harvested, animals were culled, and survival depended on preparation and protection. But Samhain wasn’t just practical. It was profoundly spiritual.

The Celts didn’t see time as linear. They saw it as cyclical, and Samhain was the hinge—the moment when the old year died and the new one began. It was a liminal space, a crack in the calendar where the veil between worlds thinned and the dead could walk among the living.

This wasn’t just folklore whispered in candlelight—it was ritual, practiced across what is now Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Sacred sites like the Hill of Tara in County Meath, Ireland—once the seat of High Kings—and the Beltany Stone Circle in County Donegal were believed to be spiritually charged locations where the veil was thinnest. These weren’t just ceremonial—they were cosmological crossroads.

Samhain wasn’t a party. It was a reckoning.

What Did They Do at Samhain?

Twin Bonfires: Lit on hilltops and sacred sites, these fires were used for purification and protection. People and livestock were led between them to cleanse and bless them for the harsh winter ahead. At sites like Tlachtga in County Meath, twin bonfires blazed atop sacred hills. Walking between them wasn’t just ritual—it was a spiritual cleanse, a way to burn away misfortune and disease before the long winter.